Mother / Work

Art / Labour

Exhibition essay by Zoe Freney

MOTHER is a verb and a noun; to do and to be. The artists in this exhibition explore a diversity of ways to be mothers and to engage in the work of mothering, through expanded drawing practices including works on paper, painting, sculpture, performance and photography. They contribute to an ongoing project led by artist mothers, bringing to light what has long been hidden by the Western canons of art history and feminism, and from mainstream modes of representation.[i] Through their work the artists in MOTHER explore a range of maternal experiences beyond the idealised, sentimentalised or commercialised to instead admit to the struggles, the spilt milk, blood and tears, the ‘full, messy and beautiful,’ life of being and doing.[ii]

The labours of mothering and making art are twin points of adversity in Australia. A study recently released by RMIT and the University of Melbourne finds artists earn on average just less than $14000 a year from their arts practices. While women make up 74% of this workforce, their average earnings are 47% less than those of their male counterparts.[iii] The Visual Arts Work report recognises structural issues that lead to the gender pay gap and the failure of women to ‘progress… to “established” career stages in line with men.’[iv] To address these issues, the report’s recommendations include, ‘Affordable childcare for artists with care-giving responsibilities…’[v] It is hard to justify paying for childcare in order to continue a precarious and speculative art practice, against still extant patriarchal ideologies of women as natural carers.

The financial struggles of mothering and art working are paralleled by the sudden paucity of time, when hours are no longer one’s own, and by the catastrophe of identity brought about by becoming mother, when even one’s own self must be shared. This coalescence of intensities can amount to an overwhelming experience, an ongoing interruption to normal life. Or a new normal, where the newness carries meaning, where the potentiality and futurity of parenting and the relationality of caring for others is valued and remunerated.

Lisa Baraitser in her exploration of the maternal subject writes how the ‘extremities’ of motherhood create new ‘raw materials,’ new ways for the mother to experience herself and others.[vi] In Heave, 2024 Fran Callen harnesses the stuff of daily routines as well as more seismic family events along with materials collected and accrued by herself and her children. These are laid down on canvas-as-kitchen-table, and grow up like plaster stalagmites, the accretions of a maternal life. In her studio, a space for ritual and creation, Alexia Fisher shapes her materials without tools to impart in them the physical and emotional tension carried in her body. This way she explores contradictory states of fragility and strength, care and brutality, the temporal and permanent. [vii]

Baraitser reflects on the sensations of being caught in between states, interrupted.[viii] She re-evaluates these moments to suggest they may lead to an ‘eruption of being,’ or a new way of thinking.[ix] The intertwined figures of Sanné Mestrom’s Maternal Cosmos are physical manifestations of the profound transformations brought about through matrescence, becoming a mother. Mestrom observes that life takes on new dimensions that include strange convergences of internal and external states and conjunctions of past and present.[x] The physicality and emotions present in ‘the liminal state… of mother-becoming,’ are explored by Madeline McGregor in Touchstone, 2025.[xi] In becoming one thing there may be the experience of un-becoming something else. In this vulnerable, transitional time McGregor speaks about seeking a reference point, perhaps through connection to place and cycles of nature.

Anna Louise Richardson’s drawings also use the land and animals as metaphors for deeper emotional and existential themes including parenthood, family relationships, intergenerational exchange and settler identity.[xii] Alongside Swallows II, 2024, a close observation of the intimacies of the avian family, Nest, 2024, is a study in downy softness and care. But the intensely detailed drawing also undoes the sentimentality of the image of mother and baby bird, revealing the tangles and mess of a nest, the abject untidiness of the lived experience of care. Similarly, Jingwei Bu’s Hairy Tales 1 and 2, 2018, evoking strands of fallen hair drawn in swirling, rhythmic lines, reimagine the abject as a material and a symbol, with deep cultural and personal significance. Bu writes, hair ‘carries our DNA, our history, and our shedding selves,’ echoing ‘the cycles of life—birth, growth, and eventual dissolution—resonating with the experience of motherhood and the passage of time.’[xiii]

Notions of time, endurance and transmission of knowledge as well as deep connections to Country are evident in the work of Pitjantjatjara artists Megan Lyons and Nyunmiti Burton. Lyons comes from a long line of artists, including her grandfather, painter Tjilpi Tiger Palpatja and her Aunty Kukika Adamson who paints alongside her at the APY Art Centre Collective. Lyons paints Piltati, the Tjukurpa of the Wanampi (water snakes).[xiv] She says,

I always think about this story when I paint. Back in the old days if a woman was pregnant and was going into labour, they would take her to a cave to have the baby. My great grandmother was travelling west when she needed to stop and have her baby. Her family took her to the cave at Piltati and my grandfather was born there. That's why we became part of that story and that country. And that's why I know and paint that Tjukurpa.[xv]

Tjukurpa is central to the work of senior Pitjantjatjara woman and esteemed artist Nyunmiti Burton. She paints Kungkarangkalpa, the Seven Sisters Tjukurpa, which was first taught to her by her mother, Tinimai. Burton speaks of the importance of women leaders in sharing knowledge and culture,

When I paint, I think about my country… I think about the past and about the future. I think about my ngura (land/home), where me, my children and grandchildren live. I think about the stories my father and grandparents shared with us. And I also think about my children and grandchildren’s future, the next generation.[xvi]

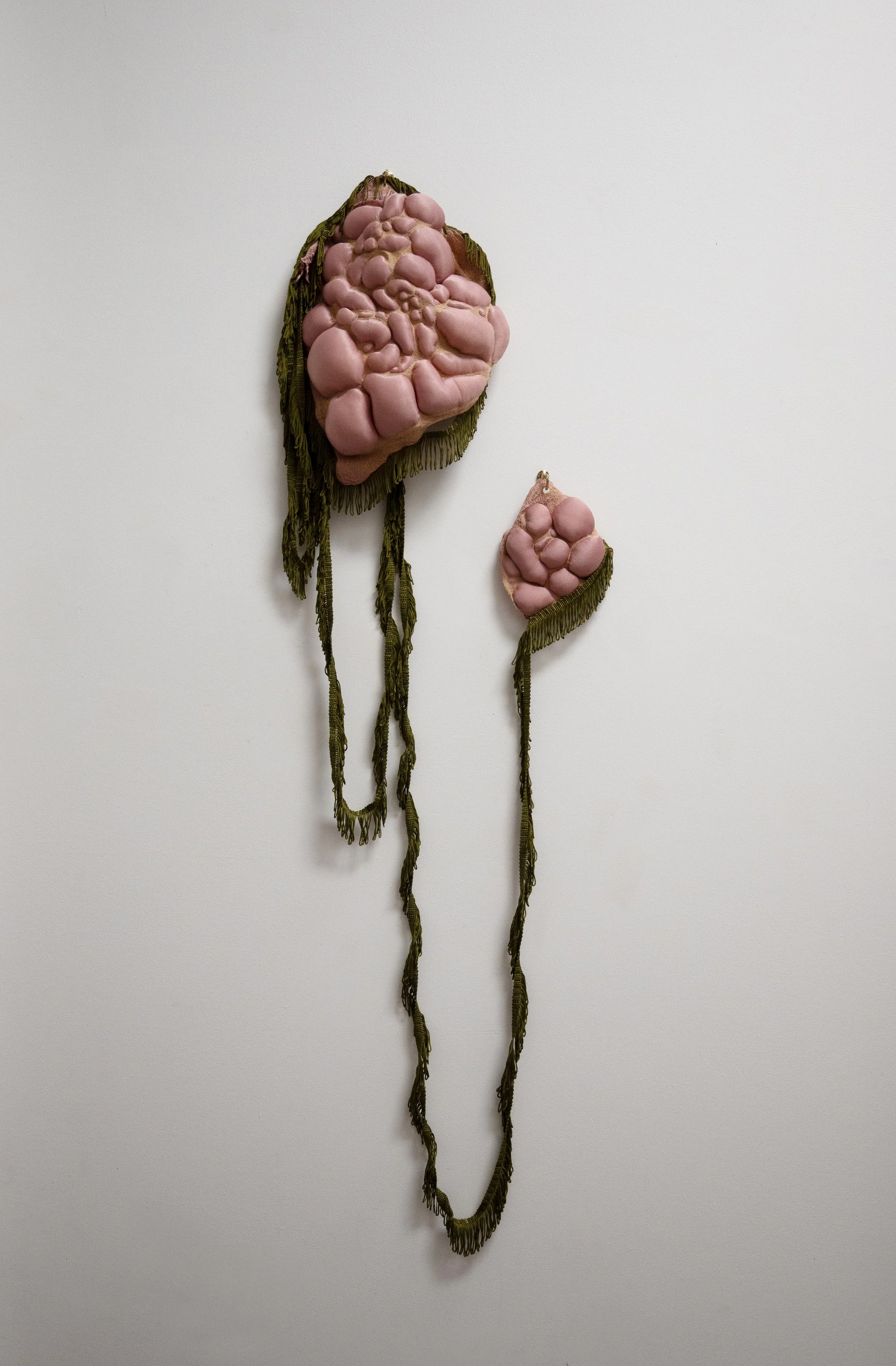

Women’s time has been described by Karen Davies as continuous, with few opportunities to take ‘time out.’[xvii] Time expressed as the ongoing labour of mothering is explored by Zoe Freney in Z and A on the couch, 2025, a pastel drawing that depicts her adult and teenage sons. Observed from a low viewpoint the subjects are seemingly oblivious to the presence of the artist, signalling their move into adulthood and the shifting maternal-child relationships. Time as constancy of care is an idea expressed by textile artist Lottie Emma. The work Mother Shield Forever and Ever, 2025, explores themes of disempowerment, resilience, and hope, shaped by her experience as a mother to a child with special needs.[xviii] Made of repurposed fabrics and using machine embroidery techniques the shield-shaped forms also recall the vulnerable folds of the body’s interior.

Harriet Body’s multidisciplinary practice is grounded in care and community and uses slow, meditative processes to explore cycles of growth and impermanence. Sonlight creates a world encircling the warm light of the central bulb, perhaps an allusion to orbits of care. Ali Noble’s multidisciplinary practice gently disrupts the hard-edged exhibition space with what she calls ‘soft-contrariness.’[xix] Textile’s sensual and poetic qualities are harnessed to cultivate colourful spaces of magic, play, and transformation.

Hettie Judah in Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood, describes how western art ‘for centuries… promoted a maternal ideal to which no flesh-and-blood woman could measure up…’[xx] In the work Dust, 2023, Atong Atem meets these impossible ideals with her own experience of motherhood and its embodied intensities. She centres the Dinka women of South Sudan and ‘explores their relationship to the rupturing history of Christianity and colonialism.’[xxi] The ambiguity of the faceless figure suggests Madonna or goddess, or the erasure of identity of the earthbound mother. Atem describes the moment of recognition of a new intersubjectivity when she was surprised to see her baby’s reflection alongside her own in a train window.[xxii]

A mother’s loss and grief is embodied in the Christian tableau of the pieta – pity or compassion - depicting the Virgin Mary cradling the lifeless body of Christ. The power of this composition lies in its contradictions: divine figures shown in human fragility, transcendence expressed through a mother’s earthly mourning. Across time, La Pietà has been reimagined to speak to war, trauma, and care, used by contemporary artists to highlight collective suffering, gendered labour, and the politics of remembrance. In Katy B Plummer’s video La Pietà, 2014, the artist cradles and sings a song explaining art to a giant dead rabbit. This is an act of resistance towards both the unachievable perfection of the Virgin Mary and the heroic genius of conceptual art. Beyond Dada, this is Mama. The capacity for invention and experiential knowledge of the mother artist exceeds patriarchal imagination. She can create.

The structural and cultural exclusions of motherhood have meant each new generation of artist mothers must reinvent ways of balancing mother work and art labour. What is at stake in this impossible balance is the exploration and representation of the full range of maternal experiences, the creative negotiation of relational subjectivities brought about by care work. But what emerges in MOTHER is the inventiveness of artist mothers, their tenacity and passion, and what they share with us of the absurd, surreal, messy, interrupted, loving, desperate, complexities of mother work.

[i] Martina Mullaney quoted in Hettie Judah. 2022. How not to exclude artist mothers (and other parents). London: Lund Humphries.

[ii] ‘Martha’, artist quoted in Hettie Judah. 2023. ‘Full, messy and beautiful,’ Unit London. https://unitlondon.com/2023-05-31/hettie-judah-full-messy-and-beautiful/ (viewed 19/4/25).

[iii] Hannah Story. 2025. ‘New study of Australian artists finds average income from art is only $14k.’ ABC, April 2. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-04-02/rmit-study-australian-artists-arts-workers-average-income/105126138# (viewed 19/4/25).

[iv] Grace McQuilten, Jenny Lye, Kate MacNeill, Chloë Powell, and Marnie Badham. 2025. Visual Arts Work: Key Research Findings, Implications and Proposed Actions. Melbourne: RMIT University and University of Melbourne. 31.

[v] Ibid. 30.

[vi] Lisa Baraitser. 2009. Maternal Encounters: The Ethics of Interruption. East Sussex: Routledge. 3.

[vii] Alexia Fisher. 2025. Artist Statement.

[viii] Baraitser. 79.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Sanné Mestrom. 2025. Artist Statement.

[xi] Madeline McGregor. 2025. Artist Statement

[xii] Anna Louise Richardson. 2025. Artist Statement.

[xiii] Jingwei Bu. 2025. Artist Statement.

[xiv] Megan Lyons. Biography. https://www.apygallery.com/pages/megan-lyons (viewed 24/4/25).

[xv] Megan Lyons. 2025. Artist Statement.

[xvi] Nyunmiti Burton in Stories from Our Spirit: Nyunmiti Burton, Sylvia Ken, Barbara Moore quoted by Art Gallery of South Australia. https://www.agsa.sa.gov.au/education/resources-educators/resources-educators-ATSIart/tarnanthi-2021/nyunmiti-burton/ (viewed 30/4/25).

[xvii] Karen Davies quoted in Baraitser. 74-75.

[xviii] Lottie Emma. 2025. Artist Statement.

[xix] Ali Noble. 2025. Artist Statement.

[xx] Hettie Judah. 2024, Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood. London: Thames & Hudson. 19.

[xxi] Atong Atem Dust. 2023. Art Collector. https://artcollector.net.au/gallery-event/atong-atem-dust/ (viewed 24/4/25).

[xxii] Atong Atem quoted in Namilla Benson. 2024. The Art of… Australian Broadcasting Corporation, August.